In his remarkable memoir of the Second World War: Quartered Safe Out Here, George MacDonald Fraser shares his experiences in the Burma Campaign as a 19-year-old private in the Border Regiment fighting the Japanese during 1944-45. In this work, he deals with many of the universal experiences of men in combat; he notes:

Nobody in his right mind longs for battle or sudden death.

But once you’ve trod the wild ways, you can never get them out of your system.

Fifty years ago, this week, I returned home from Thailand, having spent the first four months of my year there flying combat missions over Cambodia.

The day I left the war zone lingers in my mind. On 19 April 1974, I boarded a “Freedom Bird” heading home. That day, my friends turned out to see me off as I returned to “The World,” as we called it. G.I.s had performed this ritual many times since the war began.

“Sawadee, the Thais said, meaning goodbye and hello,” as if we were always together.

We popped champagne and passed it around. Friends placed Thai Sawadee necklaces around my neck, and my friends said more quick goodbyes. It was all so fast, almost a blur, and then over. I boarded the “Freedom Bird” aircraft taking us home, stowed my carry-on gear, and strapped in for takeoff. The C-141 aircraft, full of men and women of all ranks and specialties, taxied into position and began the takeoff roll: Udorn, where I had lived, rushed by the windows.

Goodbye to Thailand.

The bird broke ground. Like a volcano erupting, a huge cheer roared through the airframe. “SAWADEE,” we were on our way home. Sawadee didn’t mean goodbye; it meant we would always be together. I did not fully understand what always being together meant at the time.

Today, I know it is PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Many men and women from Korea, Vietnam, and the Afghanistan-Iraq war eras have experienced PTSD. While my family probably doesn’t think I have PTSD, I do. To be clear on this, anyone who was in combat experiences some form of PTSD. This condition was called “shell shock” during World War I and “combat fatigue” in World War II. PTSD can involve thoughts, memories, distressing dreams, or flashbacks of events. Flashbacks may be so vivid that people relive traumatic experiences. PTSD is a spectrum of reactions ranging from a bit of difficulty adjusting to non-combat or civilian life to severe depression that may lead to suicide.

There are many resources for those still trying to deal with this experience, and it is essential to seek help. One of the most valuable resources is the American Institute of Stress. The institute has a connection to Geneva: Dr. Kathy Platoni. A practicing clinical psychologist, Dr. Platoni retired from the U.S. Army with the rank of Colonel in October of 2013 and is a graduate of William Smith College (B.S., 1974). As an Army Reserve clinical psychologist, she deployed on four times in war and is a survivor of the tragic Ft. Hood Massacre in November 2009. Dr. Platoni works with the military, first responders, and others who served in combat or have experienced other trauma. She is considered one of the leading experts in treating PTSD in the country. Anyone having issues with combat or other trauma should check out the American Institute for Stress, found online at https://www.stress.org/.

Time in combat changes one.

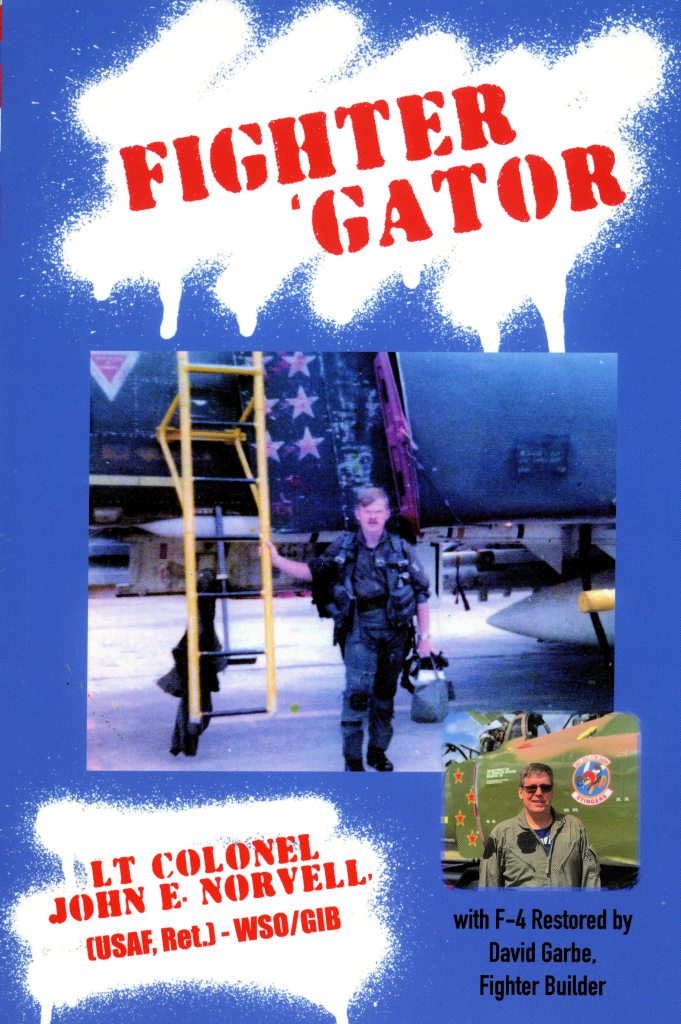

For me, it included many things: honing my flying skills in the F-4, learning to deal with the world of combat, and being away from my wife, which was a difficult thing to do. It also meant dealing with coming home.

It was hard to leave these men I had gotten to know so well. We ate together, flew together, celebrated together, and shared some amazing experiences in the air. When we had finished flying, we shared a few brews—well, maybe more than a few. I never again experienced a bond like the one we forged in combat. I will never forget that time so long ago.

It is true: “… once you’ve trod the wild ways, you can never get them out of your system.”