Fifty years ago, on January 27, 1973, the United States and North Vietnam agreed to a ceasefire to withdraw American military forces from South Vietnam. The agreement also released American prisoners of war (POWs) held by North Vietnam.

Operation Homecoming had three phases: the initial reception of prisoners, the airlift of prisoners to Clark Air Base in the Philippines, and finally, relocation to military hospitals. POWs were released based on the length of time in prison; the first group had spent six to eight years as prisoners of war. The last POWs were turned over to allied hands on March 29, 1973, raising the total number of Americans returned to 591. Of the POWs repatriated to the United States, a total of 325 served in the United States Air Force.

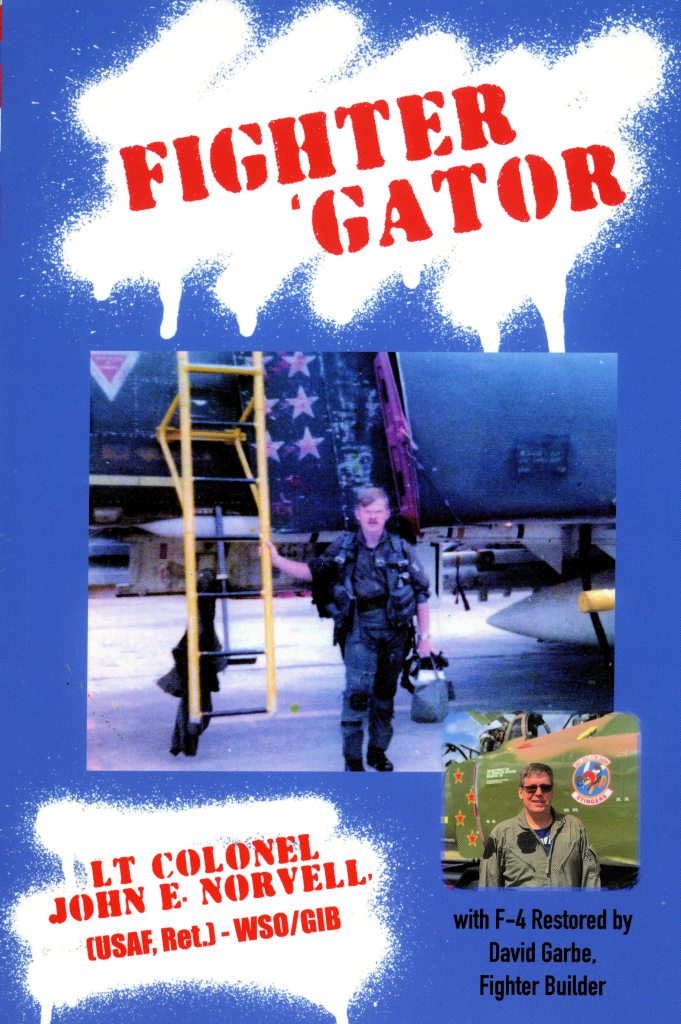

In 1973, at the time of the release, I was a captain navigator at Luke Air Force Base outside Phoenix, Arizona, going through upgrade training to fly in the backseat of the F-4 Phantom II. I knew that many of the POWs were Air Force fliers who had been shot down and captured. The F-4 fighters were the highest number of fixed-wing aircraft shot down in the Vietnam Air War. Then, I wore a POW bracelet. Then, many aircrew members wore POW bracelets and Missing in Action (MIA) bracelets. This kept the POWs in our hearts and minds, even if we did not know them personally. I wore this bracelet with the understanding that I would keep it on until the person returned from the war. My bracelet had the name of an Air Force captain lost in 1968 over North Vietnam. I received this bracelet right after I had completed the mock POW camp training part of the basic survival school at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington.

This training, called SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape), taught the basic survival skills of dealing with bailing out over a wilderness area: land navigation, camouflage, communication techniques, and how to improvise needed tools and equipment. But since the U.S. was in the middle of a major air war in Vietnam, it also included a mock POW camp to prepare aircrew members for the possibility of capture. Many of the POWs who returned wrote memoirs about the techniques they used to communicate and survive the long, dark days in the Hanoi Hilton. They learned them in this training.

As the POWS returned home, we learned that one of them would arrive at Sky Harbor airport in Phoenix one evening in April 1973. We decided to go to the airport and welcome him home. This period was a time when most Americans did not think highly of those of us who were serving. It was common to hear people ask men in uniform, “Have you killed any babies this week.” Given the hostile attitude to those who served, we felt it was essential to be there and give that man a proper welcome home.

We drove to the airport and joined a small crowd at the gate. Today it would be huge, but those were different times. Some folks had flags and signs, and we weren’t exactly sure who the POW was. His family greeted him once he left the arrival area, and a cheer rose from the crowd. Many folks had tears in their eyes. We who were at Sky Harbor that night will never forget this event.

Later in 1974, when I, too, had flown combat missions over Cambodia and returned home, I met several of these men, some of whom I flew with in the F-4 and later taught with while at the Air Force Academy in the history department. Many called these men heroes. But were these men perfect? Many were flawed, but they kept the faith. They went to war in Vietnam with little concern for themselves and their eyes wide open. They knew what they were getting into. They did their duty when so many did not. It was a very selfless thing to do.

I can think of no better definition of heroes.